Friends!

A few weeks ago, skibidi and tradwife made their inaugural appearances in the Cambridge dictionary, formally ratifying their place in the English language. While the meaning of tradwife might be easily intuited, explaining skibidi to someone who isn’t terminally online is a genuine challenge (I’ve tried). One has to explain that there’s an evil toilet involved, and also ask, “Do you know the song Give It To Me by Timbaland and Nelly Furtado?” Now, thank goodness, I have an authoritative reference text to point to.

Cambridge defines skibidi (adj.) as “a word that can have different meanings such as ‘cool’ or ‘bad’, or can be used with no real meaning as a joke.” It’s notable that skibidi was afforded such ambiguity in its dictionary definition; other words with multivalent uses (“sick” as disgusting, cool, or unwell, for example) have all of their connotations listed. Gobbledygook and balderdash are used as descriptors of the nonsensical. Skibidi, in contrast, is simply a blank vessel – its meaning is completely up to you. Used in a sentence: “What was the most skibidi part?” Or, “That wasn’t very skibidi rizz of you.” (Note: Rizz, a truncation of “charisma”, was declared as the 2024 Word of the Year by the Oxford University Press).

Neologisms reflect shifts in culture and technology, and skibidi is a mirror of its time. Generation Alpha, native to the algorithmic internet, has coined a term without definitive meaning that reflects a world of accelerated media cycles, post-truth politics, and the merciless churn of exchange value-driven mass consumption – a world in which novelty, ephemerality, and spectacle can trump the necessity for mutual understanding. Though some might protest that there’s no place for semantically empty language in the dictionary, I would argue that the institution serves as much as a historical archive as it does as a reference database. To document the language of 2025 is to faithfully capture the conditions of Gen Alpha’s propensity towards absurdity – even nihilism.

Here at The Empty Cup, we listen closely to what skibidi and other examples of “brain rot” verbiage have to say; the words we’re using might tell us who we’re becoming. In Stuff for Study, Vitòria looks at the linguistic trends of Gmail automated replies and “algospeak.” In Visions of Attention, Eleanor explains the Bouba-Kiki effect, the phenomenon of ascribing visual features to phonetic feeling. And From the Trove, David digs up Metaphors We Live By by George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, an essential resource for identifying the metaphors that shape our conception of abstract ideas like love, conflict, and freedom.

Of course, we’re always in the practice of collective meaning-making at our in-person gatherings. Join us for our upcoming seminar on BIRDSONG, where we'll train our ears to nonhuman languages. Or, sign up for a fall ATTENTION LAB, where we explore, experiment with, and give language to forms of attention that can help us build a shared world.

Skibidily yours,

Czarina Ramos

Managing Editor

Stuff for Study: Online Language

Readings and other resources for continued learning on attention and politics

Do you really want to get rid of your TikTok voice? — Claire Murashima, Leila Fadel and Steve Inskeep for NPR

Reply? The lexical nudge of automated Gmail responses — Sophie Haigney for The Baffler

Leg booty, panoramic, seggs: we're speaking for the algorithm now — Melina Delkic for The New York Times

Read receipts are extracting our good faith in friendships — Lillian Fishman for Granta

The irresistible case for brain rot language — Kaitlyn Tiffany for The Atlantic

Coincidences are linguistic adhesives — the algorithm is killing them –

for The Etymology Nerd on Substack

- Vitòria Oliveira

Visions of Attention

An archive of images and mini-essays on the myriad modes of attention

Looks Like It Sounds

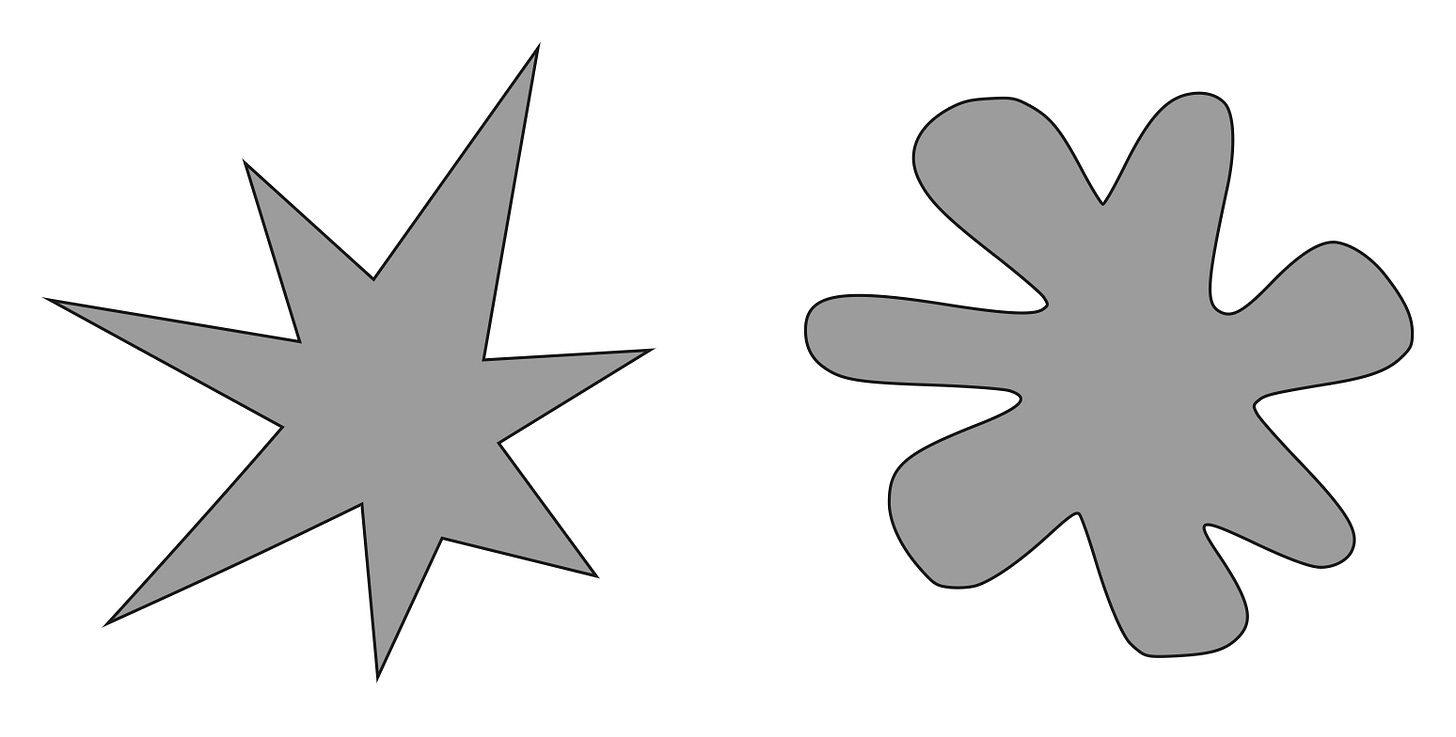

Meet Bouba and Kiki. Who’s who? You probably already know. Without prompting, over 95% of people instinctively assign “Kiki” to the jagged, spiky shape and “Bouba” to the soft, round one. But why?

What we know today as the Bouba-Kiki effect was first documented in 1929 by German psychologist Wolfgang Köhler. Using the pseudowords “takete” and “maluma,” Köhler found that people consistently paired “takete" with angular shapes and “maluma” with rounded ones. Nearly a century later, the words have changed, but the findings persist – replicated across languages, cultures, and even among pre-linguistic children. The effect is a doorway into the distinctive architecture of human language and attention.

Our brains seek harmony and congruence, intuiting patterns that often make intuitive sense, mapping sound to shape, movement to emotion, sensation to meaning. The sharp staccato syllables of “Kiki” feel like they belong to something pointed; “Bouba” rolls gently off the tongue, echoing the curve it's meant to describe.

Researchers have turned to this effect to explore the origins and evolution of language itself, challenging the notion that words are random or disconnected from the concepts they aim to convey. Instead, Bouba and Kiki seem to further bond attention and language in their mutually constitutive powers – each shaping and shaped by the other – in service of a deeper drive for coherence: a quiet, intuitive knowledge that some things just fit.

-

From the Trove

Long-form recommendations from the Friends of Attention’s collaborative Attention Trove archive

By Way of Metaphor

One of the most pervasive ways language shapes attention is through the metaphors that scaffold our world. Lakoff and Johnson’s book Metaphors We Live By (1980) illustrates this. You’ll be surprised how much of our everyday, non-figurative language is metaphorical and shapes our interactions by metaphor’s logic. Consider the opening example: the fact that argument is ordinarily conceived through war metaphors makes us argue as if we were at war. Lakoff and Johnson write: “We don’t just talk about arguments in terms of war. We can actually win or lose arguments… The language of argument is not poetic, fanciful, or rhetorical; it is literal. We talk about arguments that way because we conceive of them that way – and we act according to the way we conceive of things…”

Reading their analyses of the metaphors undergirding our understanding of “love”, “ideas”, emotion – indeed, “understanding” itself – will train you to notice the conceptual systems that subliminally script our behavior. Attention mirrors language’s metaphorical nature, always seeing one thing in terms of another. (Indeed, see how many metaphors we've used in this gloss: scaffolds, scripts, mirrors…) And if language shapes the attention with which we inhabit and shape the world, it stands to reason that changing our language has more than figurative powers. The question then becomes: What metaphors do we want to live by?

- David Landes

IRL

Tue, September 16th: BIRDSONG, an in-person 3-week seminar where we will attune our senses to birds — not as objects of study, but as guides in the practice of attention.

Wed, September 17th: ATTENTION LAB: STUDY, our experiential workshop dedicated to the joint exploration of radical human attention, with a special focus on STUDY's role in Attention Activism.

Find more workshops, events, and gatherings here!